[Update: You can browse all hypergrid-enabled public OpenSim grids with Hyperica, the directory of hypergrid destinations [1]. Directory indexes more than 100 shopping and freebie store locations. Updated hypergrid travel directions here [2].]

According to a recent Piper Jaffray report [3], US virtual good sales will total $621 million in 2009 — up 134 percent from 2008’s $265 million. And this total will rise to nearly $2.5 billion by 2013. The Asian markets are even further ahead. Research firm Plus Eight Star Ltd. estimates the size of the Asian market at $5 billion [4].

But as the market grows, so does the number of companies competing for the virtual customers.

A great deal of money continues to flow into the sector — more than half a billion dollars in 2008. And, in the second quarter of this year, $237 million was invested in companies that produce virtual goods, according to a July report by research firm Engage Digital Media [5].

But that doesn’t mean that every company looking to sell virtual goods can immediately find a market.

Take for example, Second Life, one of the more successful platforms in which independent companies can sell virtual goods.

According to the company, the second quarter of 2009 showed a record high of $144 million dollars in user-to-user transactions, almost double the amount during the same period in 2008. According to the company, this marks six quarters of consecutive growth. That puts the size of Second Life’s economy at around half a billion dollars — making it the “largest virtual economy in the industry,” according to the company.

But not everyone benefited equally.

According to data released in September by Linden Research Inc. [6], almost 68,000 user accounts had positive cashflow in the month of August, meaning that they made money in Second Life. Of those, only 219 made more than $5,000. Another 264 users made between $2,000 and $5,000 that month. (Almost 1 million users total had logged into Second Life during that time period.) “Several” people make more than $1 million a year, according to former Linden Lab VP Robin Harper — of these most engage in virtual real estate, but one of Second Life’s top ten earners is in the virtual goods business, she said [7].

As the virtual goods market continues to grow, and evolve, there are a number of factors that affect profitability — factors which are likely to be influenced by the technological and changes affecting virtual worlds. These include marketing and branding, distribution networks, service, scarcity, and value.

Value

The concept of “virtual value” is a strange one. After all, does a virtual sword actually any intrinsic value at all? It has no physical existence, just a picture in a video game — like one of the building blocks in Tetris, or one of the dots eaten by PacMan.

But, in fact, a virtual good can have value in several dimensions, including entertainment value, emotional value, social value, and utility value.

A movie, for example, or an electronic book are examples of virtual goods which have entertainment value. The consumer enjoys the process of watching the movie, or reading the book, and may be entertained further when remembering it, or talking about it with friends. Similarly, a virtual sword may provide entertainment value, allowing a consumer to have more fun inside a role playing game.

A movie can also change a viewer’s emotional state, eliciting feelings of sadness, or fear, or amusement. Dressing an avatar in a sexy outfit may make the consumer feel more confident and more attractive. A virtual puppy may help the owner feel warm and fuzzy inside.

If the consumer is in a virtual world occupied by other people, then virtual objects also have social value. A fashionable outfit may make the consumer more attractive to others. A funky hat could be a conversation starter. A virtual gift may repair a friendship or spark a new relationship. Virtual objects may also allow users to share experiences in order to further their relationships. For example, friends may play virtual golf together, or climb virtual mountains. Virtual objects can also serve as signs of group affiliation. For example, certain avatar shapes signal that the wearers belong to particular role-playing communities. Business suits indicate that they are in the virtual world to do business.

Finally, virtual objects can often be useful. For example, a virtual PowerPoint projector can be used to show slides at virtual meetings. Translating devices are common throughout the virtual worlds, enabling users from different countries to communicate with one another. Virtual objects can serve educational purposes, help with communication and collaboration, and improve productivity. Virtual objects can also be used to model real world structures and events. Architects use virtual houses, for example, to allow customers to do walk-throughs and make changes before construction begins. And virtual environments can be used in conjunction with real-world sensors to monitor energy usage [8], or to track whether machinery in a factory is performing as it’s supposed to.

[9]

[9]In general, the price of an object is related to the value it holds for the buyer.

Virtual goods manufacturers looking to increase the value of a product may look for ways to make it more entertaining or more useful, have a stronger emotional impact, or more socially relevant.

Value alone is not always enough, however, to create a sustainable virtual goods business.

A consumer making a decision in a vacuum may make an offer based on what value the object represents to them. But in practice, buyers will also consider the price of other similar items, the effort it took to produce the item, and many other factors.

For producers of virtual goods, this could be a substantial problem, as almost no effort is required at all to produce additional copies of a virtual item. In addition, similar items may be available for free.

Fortunately for virtual goods creators, there are other ways of increasing the price consumers are willing to pay for a virtual product.

Marketing and branding

Much of the value of a virtual good is in the brand value associated with it. In much the same way that an expensive brand of aspirin seems to work better than the generic alternatives — even though the ingredients are exactly the same — so a branded virtual good can sometimes satisfy a buyer better, regardless of the underlying value of the product. As virtual world brands develop and evolve, the prices for these products will increase.

However, some traditional manufacturers may start to distribute virtual versions of their products at a free or low cost as a promotion.

To set themselves apart, virtual good producers may consider adding features to their products that would not be possible in the physical world. These include textures, fabrics or shapes that would not work in reality, as well as scripted actions — such as changing colors. Today, additional scripts can slow down the performance of virtual worlds, but as technology continues to improve, virtual goods are likely to become increasingly complex and interactive.

Traditional marketing and branding techniques can also be used successfully in virtual worlds. These include celebrity endorsements, guerrilla marketing stunts, viral campaigns, advertising, media placements, charitable activities and event sponsorships.

At the beginning, virtual goods manufacturers may have an advantage in these marketing efforts over their traditional counterparts because of better understanding of local market conditions and requirements. However, at some point this expertise will percolate out to marketing and advertising agencies.

History demonstrates, however, that there is always room for new players when the technology platform is evolving. The emergence of the Internet brought forth Amazon, eBay, PayPal, Facebook — and traditional companies have not been able to compete successfully against these innovators in their industries. And, as technology evolves, new market voids are created — and new companies and new brands emerge.

Successful marketing efforts require that a brand has a distinctive and consistent identity. Today, many virtual worlds make it difficult to brand products. In Second Life, for example, the creator of an item is identified by avatar name, and it’s not easy to reassign creator status to a third party, as companies would need to do in work-for-hire situations.

In addition, it may be difficult for brands to identify a clear brand advantage inside a virtual world. For example, in traditional marketing, a brand may position itself as using more expensive, higher-quality ingredients than other brands. Or it may have higher manufacturing standards and better quality control. Brands can also set themselves apart with characteristics that are difficult to copy — or are perceived to be difficult to copy. For example, a brand may boast of a secret recipe or better flavor — even if in reality customers are not able to distinguish them in a blind taste test. (See Psychology Today: “Even Better Than the Real Thing.” [10])

In a virtual environment many of these considerations do not apply. For example, customers of a high-end boutique may believe that the clothes sold there are made from better fabrics and will last longer than cheap knock-offs. Virtual knock-offs, however, can be made absolutely identical — up to the point where they would infringe on the other brand’s patents or copyrights. So a can of “Knock Off” soda can be identical in every respect to the can of “Brand Name” soda — except for the logo and trademark colors. More to the point, customers know this. In real life, the two cans might be identical as well, but customers will perceive a difference in taste and value whether one exists or not.

As a result, it will be very difficult for brands to set themselves apart purely on the material aspects of their virtual goods. These include size, shape, color, and weight.

A knock-off office chair can have exactly the same qualities as the brand-name chair. Brands will need to add features that are not easily duplicated — or are perceived as not easily duplicated. These include sounds — like the sound a can makes when you open it, or the soft whoosh made when you sit down in a chair. They also include animations. For example, a can of soda can include a drinking animation that feels particularly real or satisfying, or a chair can include a particularly attractive or comfortable sitting position. A brand can identify itself with these non-material features.

The most famous example of a brand identified with non-material features is Florida-based Eros, LLC [11], maker of the “SexGen” sex beds in Second Life. The beds themselves are not what is unique about the product — it is the animations that go with them that set the brand apart.

Another non-physical brand characteristic is innovation. If a brand successfully positions itself as being on the cutting edge of fashion — or of technology — then knock-offs will be perceived as training behind. Customers may be willing to pay extra to be up to the moment — even if, in reality, the clones are very close behind.

Distribution

A good distribution network can solve many problems for a virtual goods retailer. For example, Apple proved with its iTunes store that Internet users will pay for music –Â even when that music is available for free online — when there is an attractive, easy-to-use and reliable alternative.

Some virtual goods providers are making it easy for their customers to find and buy products when they want them and where they want them. Distribution channels include in-world retail stores, shopping malls, and e-commerce websites. Buying opportunities can also be embedded into social networks, games, collaboration tools, and other products and services.

Today, distribution networks are limited to individual worlds. Even in OpenSim-based platforms, where goods can be transferred from grid to grid, the major virtual product distribution platforms are currently associated with individual grids. Virtual goods can be taken to other grids, but customers need to register for accounts on the grids hosting the web-based shops in order to ensure immediate delivery. However, products purchased in-world from retail outlets may be bought by avatars from other grids, visiting by way of hypergrid teleport, and transported to other grids.

In general, retail commerce in Second Life and OpenSim is marked by a lack of information, difficulty finding goods, and difficulty in comparison shopping. There is also a frequent lack of correlation between price and quality, which can degrade the shopping experience.

The creation of a new distribution network which helps deliver products to buyers in a timely and convenient way, and which restores the relationship between price and quality, can help develop the virtual consumer culture. New distribution channels could include Web-based outlets for virtual goods, as well as in-world stores, chains, or malls.

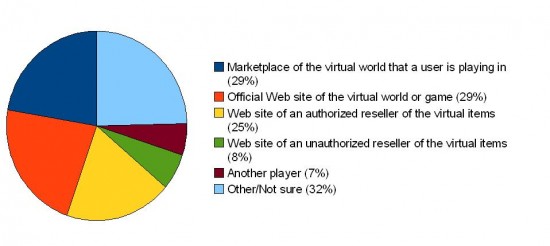

[12]

[12]

Source: Frank N. Magid Associates and PlaySpan