There was a cover story in Wired recently about how robots are going to take all our jobs. Since I started covering virtual worlds, I’ve been wondering what work was going to look like in the future. I had imagined it to look much like the work we do now, but in virtual offices.

But what happens when all the jobs are automated? What will there be left for us to do? Are we looking at a dystopian future where the lucky few have meaningful work to do, and the rest of us sit around on the dole, watching TV?

And then I thought — we’ve gone through this before.

There was a time when almost all of us were farmers. Subsistence farmers, to be exact. We romanticize it now, but subsistence farming is a really horrible existence. Visit the undeveloped, rural areas of any third-world country.

Okay, you might have a hard time finding true subsistence farming these days. Even the most remote villages are in the process of being integrated into the global economy — mobile phones, remittance payments from relatives working in the cities or overseas, mass immunization projects, clinics, traveling libraries, and international aid in times of famine or natural disaster.

Imagine a world without any of that. When one bad summer could result in your family dying of starvation. When many of your children died of disease before reaching adulthood. When horrible, unspeakable violence was a regular occurrence. (A great book came out recently, describing the dramatic decline of violence in human history, titled The Better Angles of our Nature.) When children went barefoot, and we all had one set of clothes, and water had to be carried by hand.

And this was an improvement over what we had before, too.

Anyway, imagine ourselves back in this time, and someone tells us that in the future, only 1 percent of us will be farmers. The rest of us will eat the food the farmers grow.

What will the other 99 percent do? Will they live like kings, indulging themselves in courtly intrigue and various vices, while the 1 percent who farm toil like slaves for their benefit?

But we all know what happened. The other 99 percent continued to work, including making a lot of stuff that, it turned out, farmers actually wanted — shoes, clothes, medical care, education, entertainment, vehicles, cell phones, and all the other advantages of modern life.

The transition wasn’t pretty, of course. We look back now on manufacturing work as some kind of golden age and, sure, some manufacturing jobs were nice, but there were sweatshops and long, back-breaking hours, and all sorts of horrors and abuses that came with it, as well.

Today, we tend to compare the best possible jobs of the manufacturing sector — highly paid, union jobs in clean, modern factories — with the new service sector jobs, cleaning the fryers at McDonald’s. We’re romanticizing factory jobs just like we romanticize farming.

But, overall, working in a manufacturing economy is a dramatic improvement over subsistence farming. And working in the service sector is a dramatic improvement over manufacturing. Service jobs aren’t just restaurants — they’re also medical jobs, media jobs, technology jobs, management jobs, financial jobs. They’re more interesting, and less likely to break your back. At least, if you take a few minutes every hour to stretch and maybe do a little light yoga.

Would the subsistence farmers of a few hundred years ago be able to imagine the kinds of jobs we do now? They might, if they were able to identify unfulfilled needs — shoes, medical care, education, entertainment. Or by looking to see what people at the top end of the economic spectrum were getting — court jesters, fancy clothes, royal physicians, astrologers.

We can use these two approaches today, to figure out what kind of work will be available in the future. And we also have a third option — in Second Life and similar virtual worlds we have an example of an existence where all basic needs can be instantly and inexpensively satisfied with the wave of a hand. Do you want the Mona Lisa on your wall? Wave your arm, wait for it to rezz, and there it is. But despite the fact that freebie stores are everywhere, and users can just hang out and enjoy themselves in virtual paradises and non-stop parties, many still go and find work.

I’m going to start with the Second Life case, and then move on to the other two.

Making stuff that virtual world residents want

Let’s say that the future looks a lot like Second Life or the other virtual worlds. Basic shelter, food, and clothing are free or ultra low-cost. We can all live in castles on tropical islands. Then what?

Well, it turns out that freebie clothes are a lot like thrift store clothes. They be indistinguishable from something you buy in a high-end store — especially after you’ve worn it a few times — but you know you’re wearing someone’s used donations. Given the choice, you wouldn’t buy your date clothes, or your interview suit, at the Salvation Army. Unless you were a hipster, and doing it ironically, or really really committed to recycling.

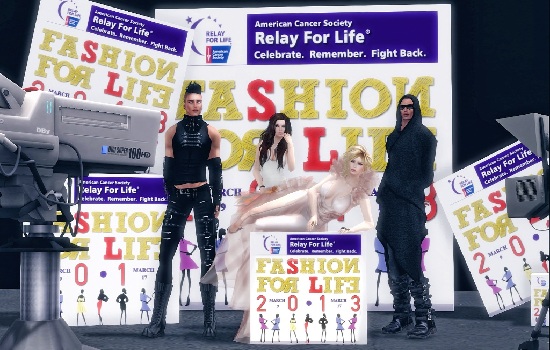

More than that, given the choice, you probably want the latest designer clothes, instead of carbon copies of last year’s fashions. And not something randomly designed by computer, but something created by someone you know or have heard of, whose career you follow.

We want to go to live music events, live poetry readings, gallery openings. A computer can make a perfect copy of the Mona Lisa, but we’d rather have something unique, special, original, something created with human intent. We want to know the story behind the things we buy.

Of course, this isn’t unique to virtual worlds. People have long preferred original art and live entertainment to reproductions, and preferred new reproductions to last season’s offerings.

The other big thing that people do in virtual worlds is they farm, and they build stuff. Farming can be very enjoyable if we do it as a hobby. There’s a reason that hobby gardening is popular everywhere, even though plastic plants look better, last longer, and don’t require upkeep.

Virtual world residents spend a lot of time with virtual crops, virtual animals, and with building virtual things. When you’re not sitting on an assembly line, even making a pair of sneakers can be a creative, satisfying experience.

So, in the future, I predict there will be lots of creative jobs, and lots of jobs associated with hobbies such as farming and making stuff.

Many of these jobs already exist. In my area, we have many gardening centers, dog grooming salons, dog obedience schools — and, of course, the entertainment industry is huge and it just keeps getting bigger. For example, despite all the moaning about illegal downloads, the movie industry saw record-high revenues last year.

What other jobs do people do in Second Life? In addition to the creative work being done, and the various programming and building and animating and texturing work, we have event organizers, escorts, fashion models, talk show hosts, community managers, role playing game managers and organizers, and so on. In general, I’d say that the jobs fall into two main categories — creative work, and people-to-people work.

Both creative work and people-to-people work require intent and attention. A book or piece of music created randomly by computer isn’t going to grab our attention or satisfy us. It might be okay for background noise in an elevator, but we’re not going to care about art unless it was created with intent, and computers won’t be able to do that. At least, not until they’re sentient and we start thinking of them as people.

Similarly, a computer might do a passable impression of a psychiatrist or a talk show host, but we’re not going to get the same degree of comfort as we do from a human being who can pay attention to us.

Stuff (and services) that only the rich have

In the old days, only nobles could have closets full of clothes, musical entertainment, and medical care. Sure, the medical care was mostly herbal remedies and leeches, and possibly worse than nothing, but at least with some of the remedies, you had the placebo effect.

What do the rich people have today that the rest of us don’t have?

To a large degree, the differences today are a matter of degree. They have slightly bigger airplane seats. They can afford more time in vacation resorts than we can. Their hotel sheets have more threads in them. They can afford experimental and unproven medical treatments.

So, the future looks bright for the resort and travel industry, and for experimental medical treatments.

But the rich can also get assistants to do a lot of jobs that normal people do themselves. They have managers, image consultants, personal stylists, publicists, career advisors, financial planners, psychics, interior decorators, therapists, tutors, personal trainers and attorneys.

The rest of us have to do all that work ourselves. We might hire a babysitter once in a while, or get someone to come in and clean our house, but we don’t employ the vast armies of support staff that the rich do.

That’s going to change. We’ll be spending less and less of our income on food and manufactured goods and routine services, and we’ll have more money to spend on our own image consultants.

So we’ll have, say, fewer jobs pushing paper for insurance companies, and more jobs helping people find clothes that make them look good.

Plus, for every job taken over by robot or computer, there will be a certain number of customers who’ll want it done by hand. Just as there are people willing to pay extra for free-range, hand-raised chickens and hand-made crafts and furniture, there will be people looking for hand-made … insurance quotes (instead of computer generated ones), hand-drawn animation, human store clerks, delivery men, nurses, waiters.

Stuff that we don’t know we want

Are there needs in your life that aren’t being met? It can be hard to tell.

When you live your life plagued by fleas, you might not know that you have a need for flea powder until you find out that such a thing exists.

All the problems I can think of right now, off the top of my head — needing to lose weight, wanting to travel more, wanting a cure for cancer — these are all problems people are working on already. Chances are, whatever problem you can think of, there’s already either a solution out there already if you have the money to pay for it, or someone’s trying to come up with something.

Looking back at today from a century in the future, will we wonder how we ever got along without personal replicators, vacations on Mars, and personal ethicists?

Consider cell phones. Would our hunter-gatherer ancestors been able to imagine them?

Well, they kind of imagined them. They imagined magical abilities and items that they’d like to have.

What magical abilities would we like to have today? You’ve got flying, invisibility… magic wands that can make anything we want appear in front of us. The ability to change our bodies at will, to look younger, or just different. The ability to see into the future. To read minds. To move things with our minds.

Each of these abilities might result in the creation of a whole new industry — as the wish to fly evolved into the airline industry.

Will it take hundreds of years for us to get there? Probably not, given the accelerating pace of change.

If I was just getting started in my life, and deciding about a career, I’d be particularly worried about any job that involved moving paper or data around — finance jobs, programming, editing — and focus on work in fields that involve creativity, artisanal craftsmanship, or human interaction.

- International singers gather on Alternate Metaverse Grid for first annual International Day - April 15, 2024

- OpenSim hits new land, user highs - April 15, 2024

- Wolf Territories rolls out speech-to-text to help the hearing impaired - April 15, 2024