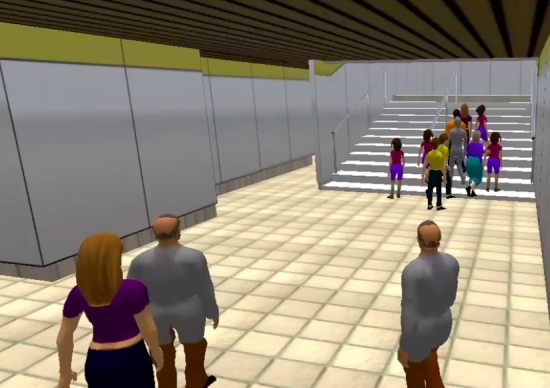

For most people, NPCs — non-player characters — are the princesses you need to save in video games, dragons you need to defeat, and shopkeepers who give advice about how to proceed in your quests.

But for David Prior, CTO at Simudyne , NPCs are a way to model emergency evacuation plans for amusement parks, hotels, banks and other large venues — even entire cities.

One customer using the technology is the European Union’s SAVE ME project, the goal of which is to develop a system that detects disasters and offers mass evacuation guidance in order to save public lives and the lives of the rescuers. The first two pilot sites will be Italy’s Colle Capretto tunnel and England’s Monument Metro station.

“With the ‘Save Me’ project, the requirement was to take people’s real world locations and actually represent those locations and behaviors and types within the 3D world,” Prior told Hypergrid Business.

To make it work, the company created a separate module to control the NPCs. OpenSim does have built-in NPC functionality, but Prior wanted to be able to run the simulations on other platforms if needed.

“We’re interested in offering some Unity delivery, especially for offering embedded clients,” he said. “And there are also the likes of Open Wonderland, Open Cobalt, or the Unreal development kit. There’s a huge raft of different options out there.”

In addition, running the NPC functionality externally eliminates the need for heavy in-world scripting, he said.

“We currently run 18 regions and will be running 111 by the end of this month,” he said. “All on a single server. We have to represent a city, and we’re not using megaregions at all.”

Scripts would not only place more load on the server, but also would stop functioning once the NPCs crossed region boundaries, he said.

Another advantage of keeping the functionality in a separate application is that it be more readily applied to other projects.

Simudyne, for example, is also working with the Bank of England and several other financial sector clients in the U.K. and the U.S. Â Other clients include the city of London, a major theme park, Â hotels and resorts, and companies in the entertainment and consumer electronic industries.

The company’s simulation software can be used to model large-scale events with transient, diverse populations, Prior said. “That’s one of the reasons why our human simulator steps up to 50,000 individuals.”

Projects typically start out with safety and evacuation training, he said.

“We’re also looking at supply chain modeling, which is something we’ve done extensively for the oil and gas industry,” he added.

Clients use the simulations to look at projected behavior and test out different designs, but, for the most part, clients don’t go in-world.

“They’re just not in that mindset yet,” Prior set.

Clients start out looking at stills or videos.

Hotels, for example, use the technology to model evacuation routes and create videos that are played to guests on the in-room television channel.

“The next step is leading people into thinking that this is not a static drawing, but an interactive space that you can use to develop policies and procedures in,” Prior said. “Then the next step is saying ‘This is cool, we can collaborate from India to the U.S., from the U.K. to Japan.”

Virtually real people

The company’s software simulates human behavior, with each NPC distinct from others. Differentiating factors include social and economic, physical disabilities, Â tendency to panic or follow parents. There’s even a variable for “bloody mindedness,” Prior said.

“That’s very much what we were doing in the European Union project,” he said.

The NPCs even interact with one another, piling at narrow exits and stepping on one another.

“We look at something called elaborated social identity modeling, which is how people perceive themselves,” he said. “And social physics, which is longer term, more community-oriented.”

Right now, the external human simulation software sends instructions into the OpenSim grid.

“The next phase that we’re doing is we’re trying to get their encounter data from within OpenSim fed back out to the human simulator to complete the feedback route,” he said. “Right now, they’re just puppets. Soon they’ll be reporting their encounters, which we’re quite confident we can do in short order – between two and three months. Most likely end of September.”

The bottom line

Simudyne does not release the price of any of the projects. But Prior did say that the company works in a variety of ways.

“In one model, we provide everything, soup to nuts, in a phased approach,” he said. “The server, the hardware, the design, the content, the implementation.”

That will typically run between 14 and 16 months, he said.

“On the other end of the spectrum, we have a rolling deal with one client, where we charge them a very small amount per floor to produce a 3D model, and it’s up to them to say how many floors,” he said. “They have a number of buildings regionally totalling somewhere over 800 floors.”

The length of time it takes to do a project can vary from five days to create a populated region, to as much as 18 months for a very detailed model of a building, he said.

The total cost for a project can vary from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars, depending on the scope and complexity, he said.

The company’s OpenSim grid is run on a dedicated private server, as a staging area for clients. When the project is complete, the company puts everything together in a package and ships the hardware to clients.

The company has three designers on staff, builders, two of whom are based in the U.K. and one in Scandinavia. Â There is also a 3D artist and a developer, both of whom are based in Boston. Prior himself works all over the world, he said.

The company also uses outside contractors for the software development, but finding freelance builders has been harder.

“Even if someone passes an interview with flying colors and builds something right in front of you, it can be hard to get them to work and not to treat it as a game,” Prior said.

Simudyne’s Avatar Control Module from Justin Lyon on Vimeo.

- Classic metaverse books on sale now at Amazon - May 16, 2024

- All OpenSim stats drop on grid outages - May 15, 2024

- 3rd Rock Grid residents find new homes on ZetaWorlds - May 14, 2024