An overview for those who haven’t used one yet

So I was fortunate enough to have gotten on the developer program for the HoloLens.

Was it hard? I don’t know. I just filled out my application and got in line.

My number finally came up, and I’ve had my developer kit for about a week.

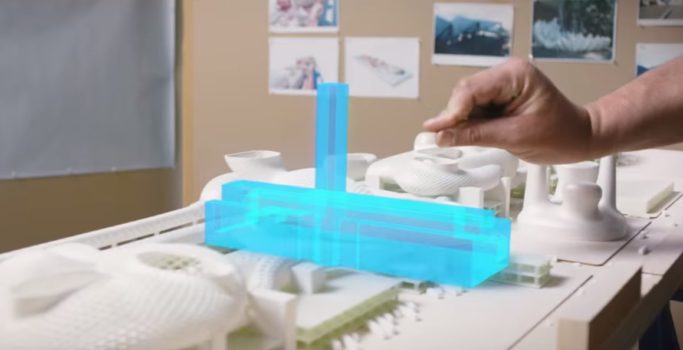

For my day job, I work in a constantly evolving tech company – Mirada Studio — a transmedia company that produces a range of creative storytelling approaches that took us through music videos, commercials, feature films, and now into the emerging worlds of interactive digital real-world experiential entertainment and interaction.

I, my coworkers, and most of my personal and professional associates are really tech-savvy people.

Many of us had an educated idea what to expect, but you really don’t know HoloLens until you actually use HoloLens. There were a number of somewhat startling revelations, some that I experienced, and many that were experienced by the dozens of people that have used mine for a few minutes here or there. This article will cover a few of them.

Spatial awareness

It really cannot be overstated how exceptional the spatial awareness of this device is. It’s quick, it remembers, and it’s so precise it surpasses all reasonable expectations.

From a hardware standpoint, the HoloLens contains what amounts to two Kinect-like sensors mounted to either side of the visor, an infrared depth sensor and a motion sensor, all of which are processed by what Microsoft calls the HPU or the Holographic Processing Unit.

The HPU processes the sensor and location data in hardware, instead of the software-based approach that the competing Google Tango platform uses.

What this means is that the mapping functions are rapid, regularly updated, and far more robust than anything you’ve experienced on another device.

If a hologram is located on a desk, for instance, you can’t move your head fast enough to make that object slide.

Some of the most savvy folks that I’ve shown my HoloLens to have been blown away by how astoundingly rock-solid the tracking is. Reflective and semi-reflective surfaces are, predictably, the enemies of this. Metallic surfaces, glass, and mirrors will cause hiccups in tracking or make areas hard to get geometry reconstruction from, which means holograms won’t “stick” there.

From a spatial memory perspective, what Microsoft has done in HoloLens is also unique versus other solutions that I’ve worked with.

An individual hologram lives within a small “sub-space” where it is understood in high resolution relationship to its environment. Many of these sub-spaces may exist, and as you travel around an area – say, an office building or your home – the entire area is mapped out including connections to the smaller sub-spaces. These maps are updated, and the individual relationships of the sub-spaces are updated to one another.

On a Tango device, if you place an object in a space, wander around for a while, and then return, you’ll typically find that the object has wandered slightly. It’ll be close — Tango does a great job of maintaining a good camera position solution — but it will often have drifted by a few inches. This is due to the space and movement being understood as a single space and one continuous movement.

I’ve seen no such drift on the HoloLens — their approach to spatial understanding is remarkable.

Additionally, thanks to understanding the geometry of your environment, renders are occluded by foreground objects. This is a really remarkable thing that you have to see to get just how powerful it is. Other platforms that I’ve built apps in provide this but this is so powerful, so fast, and so comparatively accurate that it’s quite compelling.

HoloLens remembers individual spaces in relation to what WiFi network you’re attached to. This way, it’s quick for it to find where it is in your home, your office, or a client’s office. I’m not sure that it’s actually doing this purely via WiFi – but the WiFi network name is used to help you identify which spaces it remembers, and it definitely helps it quickly acquire the relevant map.

The human user experience

First experiences with HoloLens present a unique challenge. It’s not surprising, really, since the whole platform is a new paradigm in interaction.

No-one will know what to do when they first put on the headset, so passing the headset around to various people for their first time HoloLens experience is an interesting exercise.

They don’t know whether to point at things or to wave their hands or what. The gestures are easy to learn, though, small variations in technique don’t affect recognition, and Windows Holographic does a truly remarkable job of efficiently recognizing them.

Gesture recognition, both in HoloLens and in general, is tricky, and the HoloLens limit of around two-and-a-half gestures is the state of the art at the moment.

I can’t really count the “ready” gesture — the hand with the index finger extended as if to say “one moment, please” as a gesture itself since it doesn’t trigger anything by itself.

Having developed another augmented reality gestural interface in the past, there are a couple things that become obvious:

Gesture recognition is only acceptable if it’s recognized about 99.5 percent of the time. If the UI frequently misses an interaction, like a “tap,” it rapidly becomes frustrating.

Only a small handful of gestures are predictably recognized. Gestures that can be confused with other gestures have to be avoided. You have to program for finger joint proximity and changes of finger joint proximity.

HoloLens handles both of these situations well, keeping the number of gestures to a minimum and doing a great job with dependably recognizing the small set that are available. There’s a big future in improving the number of available gestures that can be dependably recognized and lots of research to be done in that area.

Traditional applications

There are a few traditional applications that will run on HoloLens at the moment. The selection grows regularly since applications don’t need to be ported explicitly to HoloLens, only to the Universal Windows Platform, provided you’re OK using them as flat panels in space.

For items where I like keeping a window open somewhere, like my Twitter feed or a news site, I almost immediately preferred HoloLens since it doesn’t occupy any real estate on my laptop screen.

Speech recognition is superb though the logic of what Cortana does with that recognition is miles from being a consumer product.

Cortana feels grafted onto HoloLens from Windows 10, rather than being an integrated part of the experience. I regularly wanted to say, “Hey, Cortana, open Bluetooth settings,” for instance, only to have a browser window open with a Bing search for “Bluetooth settings.”

Once you know what things you can say, though, it’s really expedient to use. I can type faster, for instance, glancing around and saying “select” for each key than by air-tapping on each.

When it comes to typing — ugh. There’s nothing good here, but it’s not really HoloLens’ fault.

It doesn’t even make sense as a paradigm and yet we’re constrained to it anyway because there’s nothing else that’s replaced typing yet. Voice recognition is really good here and yet talking out loud to your glasses is still not a great way to send messages. A couple misinterpreted words take *forever* to fix.

Do yourself a favor and if you’re going to need to use a keyboard very often, just pair a Bluetooth keyboard. A few words here or there are fine. Using it to feed a search is fine. For typing in the future, we’re going to need a novel interface that’s neither a traditional keyboard nor does it require us to talk out loud to ourselves.

Visual quality

People complained about the field of view. They complained enough and with loud enough voices that I was very skeptical of getting on board with the developer kit.

Of the dozens of people that I’ve shown the device to, guess how many were blown away by the experience?

All of them.

People are typically jaw-droppingly amazed by the actual experience of seeing and doing things with the HoloLens. They’re amazed by it.

And how many mentioned the field of view?

One.

And his words were, roughly, “I’ve heard people talk about this field of view being small… This is amazing!”

Because here’s the thing: You use the center of your vision to look at things. The fovea, where humans have their highest visual acuity, covers only 6 degrees of your total field of view. Visual acuity drops off steadily from there. You don’t use your peripheral vision to read text, you use it to detect movement and avoid predators.

Now, should the field of view be wider? Absolutely. I’d love it. If it was wider it’d be easier to find misplaced interfaces — yeah, you can totally lose windows – and when a window was a bit too close or too large, it’d be more graceful to take it all in at once.

Increasing the field of view will be a constant battle for augmented reality displays, just as it is for virtual reality.

Meanwhile, the resolution is good and crisp. The text is easy to read, the graphics easy to make out.

The nature of what you’re interacting with, though, makes a bare-bones comparison of HoloLens resolution versus, say, laptop resolution a very poor comparison.

If I said it was 720p, or 4k, neither would be a good way to evaluate the display quality.

The resolution is very adequate. Does that make sense? Comparing it to Vive or Rift is likewise useless — they’re very different devices aimed at very different use cases.

Headset comfort

The headset is highly adjustable. So the weight shouldn’t be on the bridge of your nose or pressed weirdly on your temples or whatever.

It’s balanced across your head, with an optional strap, presumably if you have a strangely shaped head that it wants to slide down on. The weight, then, is evenly distributed making it much more comfortable to wear.

I typically place the “halo” with the front just below my hairline and the back below the crown of my head and adjust the eyepieces so they hover just out in front of my eyes, rather than touching the bridge of my nose.

I got a lot of questions from people about how it worked without cables and how far it could be from the computer.

So it’s important to note that this thing isn’t tethered to anything, and it feels like it can’t possibly have a computer in it, even though it does. I’ve used mobile virtual reality headsets that felt heavier.

Another startling realization is that the HoloLens doesn’t get uncomfortably hot. It gets slightly warm during use, but I haven’t felt it being hot in a week of random usage testing.

I’m sure that a very aggressive program will probably challenge that — and I’ll be running it through some pretty grueling paces soon — but HoloLens isn’t heat-challenged.

A whole lot of this is likely because the heavy sensor processing that heats up a lot of other augmented reality devices has been offloaded to hardware instead of piling a major load to the main processor.

Column reprinted with permission from the Big Blue Ceiling blog.Â

- Microsoft’s HoloLens: The good, the bad and the ugly - June 30, 2016