Teesside University is piloting a quarter million pound (US $400,000) citizenship education project in OpenSim this year. The project, which will eventually involve as many as 900 high students in the UK, will be officially launched in January.

The entire project is scheduled to run for 18 months and is funded by the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

Stewart Martin, principal lecturer and national teaching fellow at the School of Social Sciences & Law at Teesside University, is heading up the project. Martin was a teacher and then head teacher — a school principal — before moving to higher education, and his latest project takes him back to his roots.

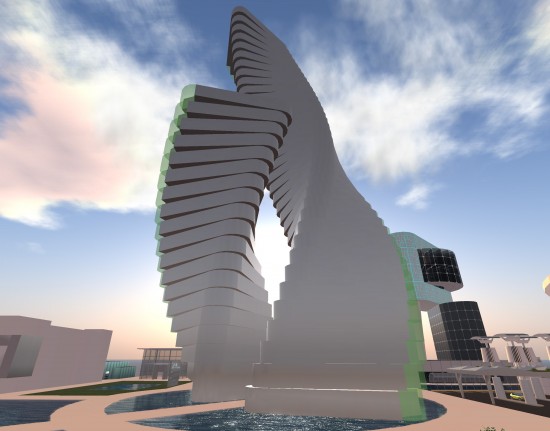

In the citizenship project, students will be able to log into a virtual environment where they can explore and discuss sensitive topics about citizenship that may be impossible to talk about in a face-to-face situation.

“Because you are face-to-face in the classroom, everyone knows who you are, and there can be consequences,” he said. “That’s a problem, especially when you want to talk about difficult issues with young people, who are very susceptible to peer pressure.”

Students in the virtual world discuss issues of relevance to today’s multi-ethnic United Kingdom.

“Suppose you have a situation where it is the tradition in your particular culture that the parents decide who the young daughter will marry,” Martin said. “And if she has a relationship with or marries someone they don’t approve of, particularly if he’s from another religion, the parents feel they have the right to beat her or even kill her.”

A scenario like this is presented to a group of students in the virtual environment.

“The brief they are given is that they’re trying to create a little civilization, a little world, a little environment in which every individual feels equally valid, equally important,” Martin said.

Because they’re in a virtual environment, the students can express themselves more than they could in real life.

“In the UK, there are groups of people who feel left out of society, disenfranchised, marginalized, and, scariest of all, some of them become radicalized,” said Martin. “Voter turnout is getting lower, which is definitely not good for democracy.”

Martin said he decided it was time to try to get young people engaged in thinking about what it means to a UK citizen. “Engaging young people in the process of citizenship, thinking about democracy, in a collaborative way, where they feel safe to speak their mind without fear of reprisal.”

Benefits of virtualization

Because the discussions take place inside a virtual environment, the developers of the virtual environment have been able to add some extra features.

For example, students have a way to indicate their emotional states when they’re in the simulated environment, so that there are no misunderstandings. In addition, they can attach a value to items under discussion — for example, they can attach the value “inhuman” to the topic of honor killings, and then provide a definition of what that value means to them.

The values, and their definitions, and the ways they are developed and used, will be observed by researchers.

“We also learn to understand what kinds of values young people think are most important in discussing citizenship, and, even more important, how do they define them,” Martin said.

The virtual environment also allows each student to get a house that they can fill with objects that represent things that matter to them.

“At the end of the experiment, one of the things we ask them to do is visit another avatar’s house, and they have to write a report,” Martin said.

The students are also required to keep a journal about their experiences going through the program, and to complete and exit interview.

In addition, they complete questionnaires before and after the experiment, measuring their empathy for people who are different from them.

Second Life vs. OpenSim

An environment like Second Life would be an attractive location for such a program, except for its limitations — for example, there are age restrictions in Second Life.

Martin would have had to get one island for students between 14 and 16, and another island for those 16 to 19.

“And it has intrinsic problems for universities and schools,” Martin added. “One of the problems is that it’s very public. You can buy an island, but it’s very expensive. And when you’re talking to parents about students who are below the age of majority, it’s very difficult to guarantee parents that these environments are free from unwanted attention from outsiders.”

In addition, the environment is controlled by Second Life.

“This is a problem for universities, when they think about protecting the data of the individuals involved,” he said. “And it’s a problem for the schools because they have to open the firewall.”

The university also considered Open Wonderland, Blue Mars and Open Cobalt for the project.

At the end of the day, Martin said, the project decided to go with the platform in which their development team, a university spinoff company called DLab, had the most expertise.

OpenSim was also attractive because it was an open source project.

“Whenever possible, I use open source software,” Martin said. “Not because I’m mean and don’t want to pay any money to anyone, but simply because a lot of my research work is international.”

Different institutions have different protocols about what kind of software researchers are allowed access to, and some institutions in emerging countries can’t afford proprietary software.

With open source software, Martin has no long-term financial commitments and is not creating financial barriers to others.

“Maintaining an island in Second Life is extremely expensive.”

In addition, OpenSim has an OAR export feature, which allows Martin to save backups of the regions.

“We need to be able to do that,” he said. “We need to be able to preserve an environment as it was left by a particular group of young people, with all the houses and inventory objects.”

In the future, researchers may return to the environment, and, like archeologists or forensic scientists, examine the scenes for clues that may have been missed the first time around.

With OpenSim, the university can run the environment on its own servers, and also give copies of the environment for schools to run behind their own firewalls.

In fact, it can make as many copies of the simulation as needed.

“Each school that joins the project will have its own environment,” he said. “They can have more than one environment.”

The university will also train teachers in how to use the environment and get the best use of it.

The teachers don’t go into the virtual world themselves — the students go in on their own.

“They’re in a classroom with their teachers in case they hit a problem,” Martin said. “But in the actual virtual world itself, the researcher will be there as an invisible agent, but is not a participant in the world.”

The researchers haven’t decided yet whether to use text communication only, or to also include voice. Voice capability will be more affected by the Internet speed at the school. In addition, text conversations are more easily recorded for later review.

“It’s quite easy to analyze that data,” Martin said. “It’s more difficult when it comes to capturing and analyzing voices.”

Graduated rollout

Today, the project is being conducted in the northeast of England, and will soon be rolling out to other parts of the UK.

“How the scenarios are responded to may be very different in Scotland or Ireland,” he said.

There are 300 students in the program now, which was the initial target of the project.

At its peak, the program is expected to include 600 to 900 students.

“We are developing and refining the environment, recruiting schools, and training teachers,” he said.

The project is now in five schools.

“I thought at first that we would need to have a lot of schools, because schools would want to contribute only a few students,” he said. “But what I found is that schools have been so enthusiastic about the project that they say, ‘Can we have all the students in the entire year group involved?’ So I don’t think I’ll need as many schools as I feared I might.”

Today, the project is in its pilot stage where, over the next few weeks, researchers will work with young people in focus groups to develop different houses for avatars, create central meeting places in which to discuss scenarios, and ensure that students have the objects that they need in the inventories.

Creative Commons

Martin said that the entire virtual environment for the citizenship project will be donated to the schools involved, and possibly to all the secondary schools in the UK.

“And I don’t see why this isn’t something we can offer to anybody in education or research,” he added.

In fact, as the project is being built out, the developers are in touch with schools and teachers to find out what particular elements they would like to see in the platform, ready for its future use in different subject areas

“Even if it’s not directly relevant to the research that we’re doing, it may be something that’s not a big task, and so may not cost very much to do,” he said. “We’ll build it in as we go along, so all schools will have it when they get their standalone version.”

For more information about the citizenship virtual environment project, contact Stewart Martin at VirtualCitizenUK@me.com.

- Kitely Mega Worlds on sale for $90 per month - July 19, 2024

- OpenSim regions up, actives down with summer heat - July 15, 2024

- People think AIs are conscious. What could this mean for bots in OpenSim? - July 12, 2024