When the announcement came out on March 12 that Linden Labs was inviting beta testers for their Oculus Rift based VR viewer, I dusted off my Oculus Rift Developers kit and signed up.

About six months ago, I tried out the first version of the Oculus Rift developer’s kit in Second Life with the CtrlAltStudio viewer.

After some trial and error to find the right combination of plastic lenses in the headset for my eyes — which are so mismatched that without the corrective lenses I do not have any depth perception — I was able to log in and see what everyone was raving about.

Even without my prescription glasses on, I perceived a view of deep perspective. Just flying over the buildings and looking down at the streets of Bay City was a revelation. I got so involved that an hour passed before I took off the headset. Feeling fatigued and slightly dizzy, I napped for three hours to recover.

These days, the CtrlAltStudio viewer has progressed, due to the efforts of David Rowe. It can be used with Kinect, Oculus Rift and Stereoscopic 3D. Since it is based on the Firestorm viewer, it can be used in both OpenSim and Second Life.

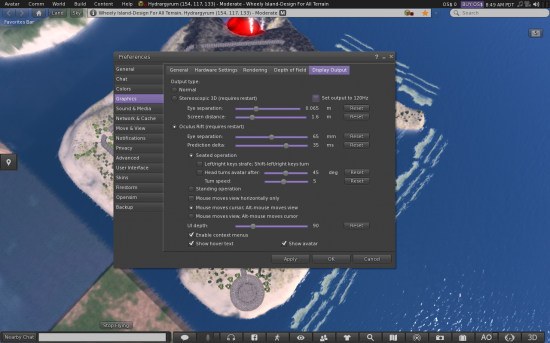

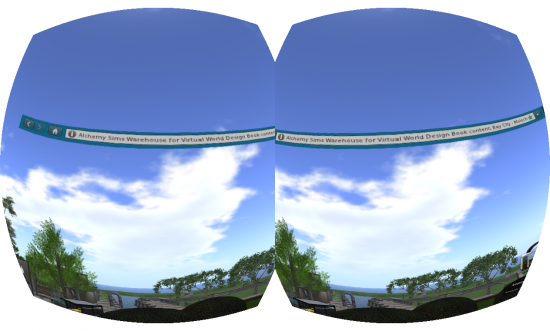

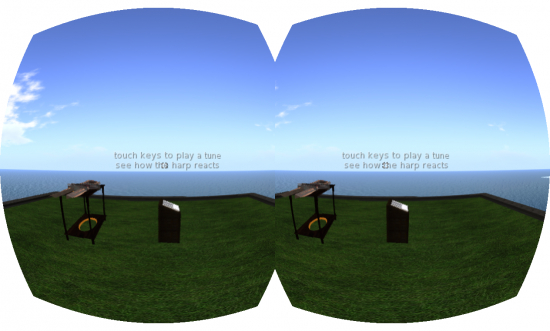

There are deep menus that provide various settings adjustments for each of these interfaces, and a nice toggle feature that lets you go from 2D to 3D easily on the bottom bar. It’s thrilling to finally see Alchemy Sims Grid in 3D.

As I was about to start exploring Second Life using their new Project Oculus Rift viewer — currently in closed beta testing — I remembered my previous experience with the CtrlAltStudio viewer and decided to exercise caution and time my visits to keep them limited to 15 minutes with an hour rest period in between. The comments on the Oculus Rift developer’s forum about side effects provide some interesting reading.

First excursion: general observations

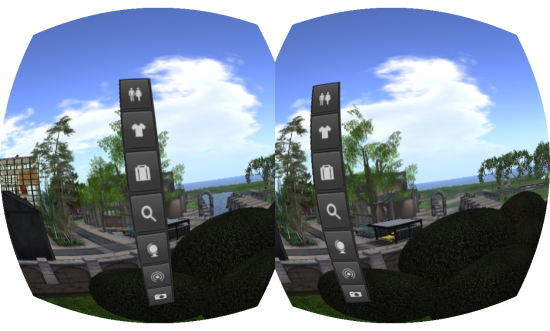

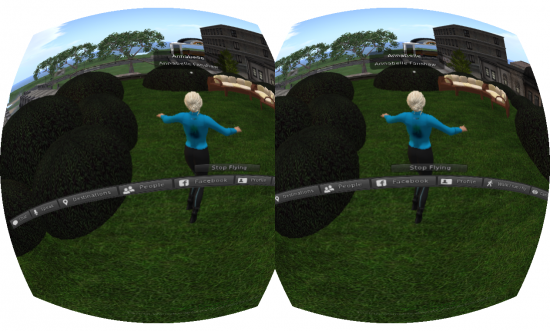

The Second Life Oculus viewer has a few enhancements over CtrlAltStudio’s. After you get set up and switch over to the head-mounted display mode, the side and bottom screen menus become simple bands of icons in space.

You will need to turn your head left or down to see them, and trying to click the mouse — much larger for easier use — on one of the buttons is a bit of a challenge at first.

In general, there was no noticeable lag in head movements and the update on the screen, although on the third excursion, I did get some juddering on my screen occasionally.

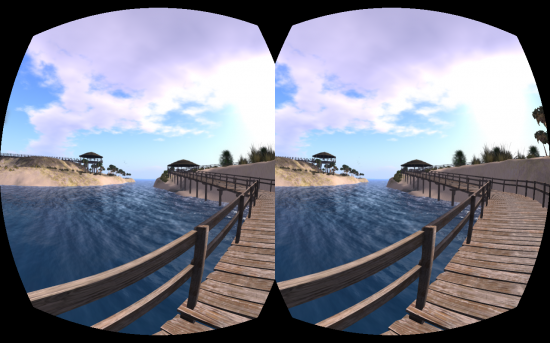

These screen grabs do not show the “screen door†effect that you will see in the Oculus Viewer, as the screen capture software only collects what’s on my computer display.

The best view was with the “Midnight†setting which reduced the “screen door†effect of the low resolution headset. After about 20 minutes, I had a slight headache, but no nausea.

Second excursion: exploring real life scale vs. virtual reality scale

Our eyes are amazing devices. Every time we look at something the muscles surrounding the lenses provide visual accommodation to bring the object of our interest into focus, while the muscles around the eyeball direct the focal point of our gaze in simultaneous synchronicity, or vergence.

As we bring in visual information to the brain, we make mental comparisons about the objects in the visual field to understand their relative scale and distance from ourselves. We understand the scale or size of an object through a variety of ways, or visual cues.

On a 2D image, scale is indicated to us in three basic ways: 1) by a familiarity with the object, we all have a general idea of how large a dinner plate is, 2) we compare the object to other objects in the scene to gauge its relative size, and 3) parallax, or the apparent scale of an object as indicated by its relative movement to other objects in the field when you change your point of view, or pan the camera.

Scale is another ballgame in the 3D stereoscopic virtual reality of the Oculus Rift. Now you are matching two virtual cameras with your eyes. Each of us has a visual standard, the distance between our two eyes, called the interpupilary distance or IPD. In the head-mounted display, there is a virtual IPD between the two virtual cameras. When that virtual IPD value is changed, the scale of the virtual world will appear to shrink or grow, without scaling the geometry. Before you play with the IPD settings, be warned — this can cause severe eyestrain. There is much more information and some interesting animations about these visual concepts here.

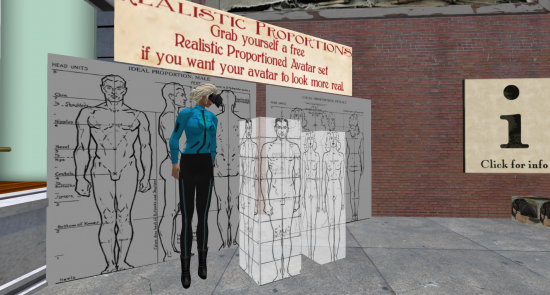

On the second excursion, I went over to The 1920’s Berlin Project- Oculus Rift and Real Scale Test Area, to make some scaling comparisons. This small area, built in real-life scale, was created by Jo Yardley, who also built the 1920’s Berlin project.

She suggests that if you are interested in discussing the potential of using the Oculus Rift in Second Life, you should join the Oculus Life group on Facebook.

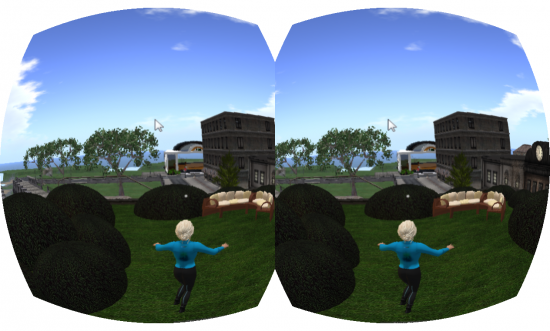

The first thing you notice is the real scale avatar display. If you have never scaled your Second Life avatar to real-life scale, it’s a big change in perception. I’m 5’5†in real life, and in Second Life, my height is well over 7’ tall. I scaled down to real-life size and put on my Oculus Rift HMD mesh model to let other avatars know I was in a different world.

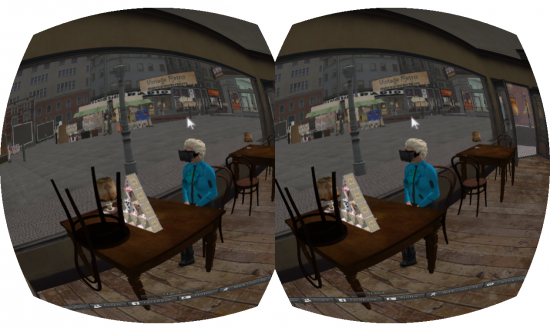

Maneuvering through the real scale environment was relatively easy, once I was sized to fit. My camera’s third person position was low enough to clear under the door frames as I entered the local bar. Sitting down at the table was not too difficult, although the posture settings on the chair animations appeared well out of my field of view, requiring me to turn my head right 90 degrees just to select a sitting animation.

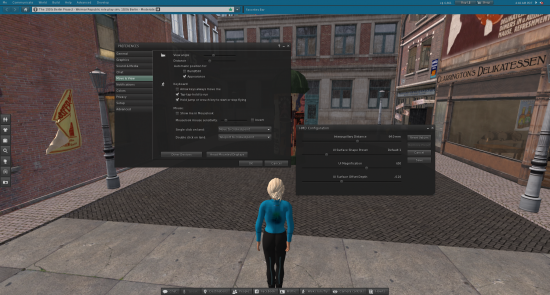

Switching back to the Second Life viewer, I tried out the Preferences-Move and View-Head Mounted Display settings menu. Unfortunately, that menu was not working, so I could not test the effect on scale. I have mentioned it in the JIRA-bug testing log, so perhaps it will be attended to soon.

Below is a screen shot of the menu in the standard 2D screen display, showing the HMD menu installed in the Second Life Oculus Rift viewer.

Third excursion: building and editing in the Oculus Rift

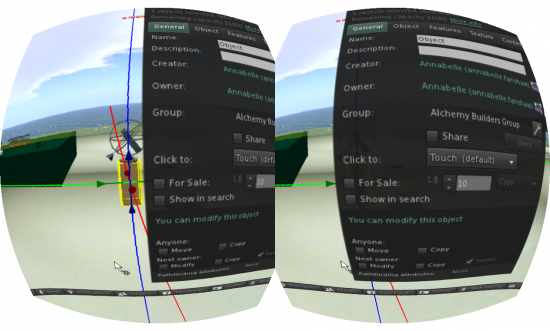

On my next outing, I tried to rezz, build and edit a few things in Second Life while using the Oculus Rift and Second Life viewer. Essentially, nothing new has been added in terms of building tools, and since you are wearing the display over your real-life field of vision, using the keyboard is difficult.

When you rezz an object and try to edit it, the edit menu appears as it would for a 2D display, and obscures half the screen. Furthermore, it appears very close to your point of view, and there is no way to move it back into the space yet.

Obviously, there is much development needed in the build interface of the Oculus Second Life viewer. Perhaps we will use motion sensors for our hands, instead of the standard mouse, and make the virtual world like this, in the near future:

Why should you use a head-mounted display?

Achieving deeper immersion is the goal in virtual reality, and with a head-mounted display like the Oculus Rift, a greater sense of that can be created.

Almost all of your entire visual field is filled with the image of a virtual world, the sense of a 2D screen is gone, and the position tracking in the headset moves the images to match your head movements creating a greater sense of being inside the world.

Who uses them?

With companies like Sony, Microsoft and Google developing head mounted devices it’s apparent that the goal is to have all of us using HMDs showing computer-generated images for at least some part of our day.

Obviously the gaming and entertainment industries see these devices as essential components to their systems and overall experience.

Manufacturing, medicine and scientific research sectors have long used virtual reality devices to help their workers collaborate with their machines, so it’s no great stretch to see these develop further.

Into the future: VR thoughts and questions

Perception, observation and the understanding of what we sense provides our personal narration for the ongoing story of our existence. How much our minds fill in, embellish, and augment varies from person to person, day to day.

What we perceive as reality, and how much of that we construct in our imaginations and dreams is a topic that has fascinated people for centuries.

It is written in the Chuang-tzu: “Once Chuang Chou dreamed that he was a butterfly. He fluttered about happily, quite pleased with the state that he was in, and knew nothing about Chuang Chou. Presently he awoke and found that he was very much Chuang Chou again. Now, did Chou dream that he was a butterfly or was the butterfly now dreaming that he was Chou?”

Now as we anticipate the imminent commercial release of several affordable and effective head-mounted display devices, what will change in our perceived realities? What effects will this kind of immersive display have on our daily sense of reality and the boundaries of virtual reality? How will using the Oculus Rift affect our perception of the “realness†of things?

When Facebook bought OculusVR last week, the CEO of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, said, “Oculus Rift is the platform of tomorrow.†Perhaps he is correct.

- Oculus viewers updated, still not building-friendly - June 6, 2014

- In-world with the Oculus Rift - March 30, 2014

- 5 tips for video tutorials and 3D simulations - February 17, 2014