On Monday, Metaplace announced that the company was shutting down its virtual world. This virtual world wasn’t the first platform of choice for enterprise users. The game-like interface, the kid-friendly avatars, and the lack of true 3D graphics — not to mention the lack of business functionality — didn’t lend the world to enterprise use.

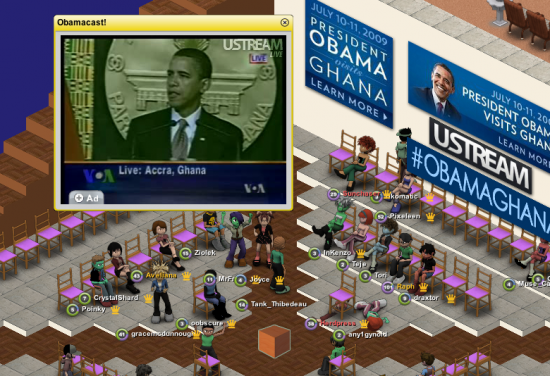

However, some organizations have been experimenting with holding events in Metaplace. In July, for example, President Barack Obama’s Ghana’s speech was simulcast in Metaplace.

Metaplace allows users to design their own virtual environments and to share them with others. In total, around 70,000 different virtual worlds have been created on the Metaplace platform.

“Over the last few months it has become apparent that Metaplace as a consumer UGC service is not gaining enough traction to be a viable product,” said Metaplace Inc. CEO Raph Koster in a statement.

In allowing users to create persistent environments, Metaplace has a lot in common with some virtual worlds — and its demise offers some lessons for enterprise users.

“We’ll see a shaking out in the virtual world’s industry in the coming months as both industry growth and increased competition leads to aggregation and attrition,” said Doug Thompson (aka Dusan Writer), CEO, Remedy Communications, and producer of Metanomics, a weekly Web and virtual world-based show that examines the serious uses of virtual world technology.

The next victim of this shaking out may be Forterra Systems Inc., which makes the OLIVE virtual world platform. Forterra focuses on the enterprise market, and counts Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman among its customers.

According to Erica Driver, an analyst at virtual worlds consultancy ThinkBalm, Forterra has just laid off 60 percent of its workforce and remaining assets are “likely to be sold.”

“It’s a sad day for the emerging immersive software sector,” she posted on Twitter.

As the sector continues to evolve, companies can take a few steps to protect themselves against possible turmoil.

Covering your assets

Where are your virtual assets stored? Are they on your servers, or servers that you control? Or are they stored on servers owned by the virtual worlds company itself?

For example, if your region is located on the Second Life grid, then Linden Lab is in control of your assets. Their recently released Second Life Enterprise platform, however, allows a company to host regions on its own servers, behind a corporate firewall.

Metaplace is of the former type of world — all content is stored on Metaplace servers. With the shutdown scheduled for January 1, users only have a few days to try to recover some of their work from Metaplace. Unfortunately, this is also prime holiday season.

If a world is hosted locally, on a company’s own servers, then even if a vendor goes out of business then the company still has its own copy of the software and content. There won’t be any further development or support, but at least the company can migrate to another platform on its own schedule.

Regardless of where the world is hosted, the ability to make backups is also crucial.

In Second Life today, there is no legal way to make backups of builds, though third-party software exists to save individual objects or inventories. Some consulting firms are also rumored to have backup programs for entire regions, but there is a great deal of controversy about this since users would be able to use this to back up all objects on a region — including objects owned by others.

As a result, companies investing time and money building up areas in Second Life will find it difficult to create backup copies of their areas.

Other platforms, especially those focused on the enterprise platform, make it easier to make backups.

Vendor lock-in

If a vendor goes out of business, will you be able to take your assets and move them to a different platform? If a vendor uses proprietary standards for the virtual world, this can be extremely difficult — as it the case with Metaplace.

Many enterprise platforms, however, support common 3D standards. For example, Forterra’s Olive can import Max, Softimage, or COLLADA 3D objects.

The OpenSim-offshoot realXtend can also import 3D objects from external design programs, as can the new Blue Mars virtual world, and Second Life and OpenSim are expected to support this functionality next year.

As a result, if one of these vendors goes out of business, users are able to move the content to another platform.

With some platforms, multiple vendors support the same set of standards. For example, the OpenSim platform is currently supported by dozens of vendors, with the number of providers rising steadily.

If one vendor goes down, many others are available to step up.

OpenSim is substantially different from most virtual world platforms in that it isn’t backed by any one company. It is designed by the open source community, with backing from Intel, IBM, and Microsoft.

This creates additional security for users, in that there are a number of different providers supporting this platform. But it also adds risks, as well, since open source communities will sometimes splinter, get distracted by other projects, or just fade away.

There have already been some signs of this with OpenSim, with the splintering off of the realXtend platform.

However, with hundreds of different worlds now running on the OpenSim platform, there is also now substantial momentum accumulating behind OpenSim, and even efforts to bridge the gaps between OpenSim and realXtend.

Meanwhile, the existence of OpenSim and realXtend provides some security for users of Second Life and Second Life Enterprise, since the same content can be used on all three platforms. Even if something were to happen to Second Life’s parent company, Linden Lab, there will be alternatives for businesses who have invested in development on the platform.

Loss of community

When a platform disappears, however, it’s not just the content that’s at risk. If a company uses a virtual world in order to interact with customers or with a larger community, then that community vanishes as well — as is now about to happen on Metaplace.

Current Metaplace users will either move to other worlds or leave virtual worlds altogether. If they get new virtual identities elsewhere, they will most likely have new user names — making it difficult, if not impossible, to recreate the community of one social network on another network.

This will be the single biggest loss that comes out of the Metaplace closure.

Companies depending on the social networks offered by virtual worlds can take some steps to protect themselves, however.

They can try to collect identifying information about their community members that exists independently of any particular network.

Today, there is no central repository of virtual identities that associates email addresses, social network user names, and other identifies with a single real identity. These repositories may evolve in the future, but until then companies should do the best they can to collect as much personally identifying information as possible and not rely completely on the social networking tools provided by the individual platforms themselves.

- OSgrid back online after extended maintenance - April 16, 2025

- Analysts predict drop in headset sales this year - March 25, 2025

- OSgrid enters immediate long-term maintenance - March 5, 2025