Investors in virtual companies listed on the Second Life Capital Exchange lost most of their money, according to a new research report.

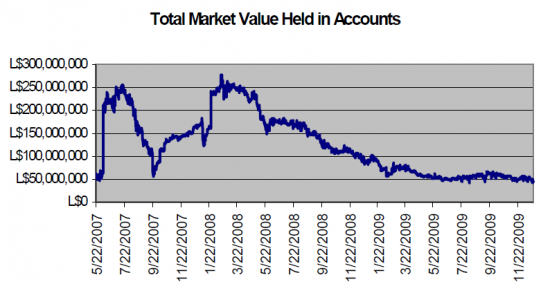

The report, which covered the time period between May 2007 and December 2009, showed that investors bought US$145,000 worth of shares in initial public offerings of virtual companies. The value of these shares fluctuated wildly. At one point, the value of these shares was over US$1 million.

But then two major decisions by Linden Lab — the shutdown of gambling on the Second Life grid and restrictions on the operations of virtual banks — combined with a wave of management scandals and falling land prices to cause the bottom to fall out of the virtual stock markets. By the end of 2009, investors had lost 71 percent of their initial investment and 19 out of 24 companies followed had been delisted, leaving only five active stocks still traded on the exchange.

The puzzle, however, isn’t why stock prices fell, but why investors put real money into make-believe companies on a make-believe stock exchange in the first place.

“One big unanswered question is … why investors gave issuers money in exchange for securities that provided very unclear benefits, without the benefit of any form of regulatory protection or transparency,” management professor Robert Bloomfield told Hypergrid Business. Bloomfield, one of the authors of the report, is the director of Cornell University’s Business Simulation Laboratory.

In its disclosure statement, SLCapEx states, “The SL Capital Exchange is a fictional stock market simulation operating for entertainment and educational purposes only.”

It’s that entertainment value that could explain why people are willing to risk their money on companies that have no oversight, Bloomfield said. After all, Second Life residents often find entertainment in working for free, he said. They organize events, manufacture goods, and work in sales and marketing.

For the most part, these activities — which are a lot like work — are not paid, or offer very little in terms of financial remuneration.

“Why not also invest in assets with little hope of a high return?” Bloomfield asked.

Where the money went

The Second Life environment is one where a great deal of real money trades hands — but there are few ways to track it.

In the virtual stock exchanges in particular, anonymous investors bought and sold stock in companies run by anonymous managers that, in turn, sold goods and services to anonymous customers.

“There wasn’t any oversight at all,” said Bloomfield. “My suspicion is that there is enough money involved for the big players to try to corrupt the process, but not enough money involved to support the hard work of developing a transparent and reliable system of reporting and self-regulation.”

For example, owners of virtual businesses in Second Life keep their Linden dollar income in their personal avatar accounts.

Many virtual companies promised to use the money they raised on Second Life virtual exchanges to rent large areas of virtual land on Second Life, then landscape it, sub-divide it, and rent it out at a profit to tenants. But there was no way for investors to really know if the land was acquired, what the rental income was — or to sue company executives for mismanagement or fraud.

“Second Life provides no method of incorporation,” said Bloomfield. “Moreover, the anonymous culture of Second Life makes legal recourse difficult.”

There was an attempt to address this issue by creating the Second Life Exchange Commission, a self-regulating organization intended to monitor companies listed on the virtual exchanges.

“But it never got anywhere and was always a source of controversy and a target of corruption accusations,” said Bloomfield.

Traditional — regulated — stock exchanges require that companies be incorporated, have boards of directors, and file audited quarterly reports. But the virtual companies on SLCapEx and other exchanges in Second Life are not required to have any legal corporate identity, are not required to have identifiable people as board of directors, and do not file any financial statements.

“Without good financial reporting, there is no way to tell whether the issuers took the investors’ money and lost it the old fashioned way — through bad strategy, bad execution or bad luck — or simply pocketed the money and claimed that things simply didn’t work out,” said Bloomfield.

The next frontier

One virtual company owner was Frank Corsi, who had three companies listed on the World Stock Exchange in Second Life, then moved the three companies to the International Stock Exchange, then to the Virtual Stock Exchange. Corsi never had a company listed on the SLCapEx, but his listed companies on the other exchanges were a focus of significant amounts of controversy.

It is this kind of controversy that he hopes to avoid with his latest venture — a virtual stock exchange that operates on the hypergrid, in the OpenSim universe.

Corsi said that his previous companies were involved in Second Life’s virtual real estate business and virtual banking.

Corsi said that he didn’t take any money out of the companies, but left all assets in the hands of his second-in-command after he left Second Life.

“I never cashed out,” he told Hypergrid Business.

Instead, the business fell apart after he left. “It became a big fiasco,” he said.

One factor was the drop in land prices — from between 15 and 18 Linden dollars a square meter to around 1 Linden dollar a square meter today.

“It makes it hard to operate in the land market there,” he said.

Today, Corsi is a president of the legally incorporated company Virtual World City, Inc., which plans to build virtual representation of actual cities, using the open source virtual world platform OpenSim.

He is also the founder of the Virtual World Business Exchange, a virtual exchange for OpenSim companies that, Corsi hopes, will avoid some of the problems seen on the exchanges in Second Life when it launches in January.

All trades on the new exchange will be denominated in G$, a fictional currency from Corsi’s CyberCoinBank. The virtual money can then be used to rent virtual land from one of Corsi’s OpenSim hosting companies.

“If something goes wrong with the stock, we’ll put the land on hold, so they can’t run away with it,” he said.

The money raised on the virtual exchange can also be used to hire designers and builders, he added. Company CEOs won’t be able to pull money out of their companies and cash out without getting approval from their investors, he said — however, the investors will be allowed to remain anonymous, as will the designers and builders.

The company CEOs will have to disclose their identities to the exchange to provide an additional measure of security.

“What we’re trying to do is squash as many loopholes as we can,” said Corsi.

But, at the end of the day, the Virtual World Business Exchange can only do so much in terms of enforcement. “Because it’s a game,” he said. “It’s not real. This will be a game stock exchange. No registration, no taxes, nothing.”

- Virtual investors lost 71% on risky SLCapEx - November 15, 2010

- TeleXLR8 wants to be the “TED” for virtual worlds - October 14, 2010

- Report: Virtual meetings growing at 80% of firms - October 1, 2010